© Laurenz Albe 2025

Table of Contents

Recently, while investigating a deadlock for a customer, I was again reminded how harmful SELECT FOR UPDATE can be for database concurrency. This is nothing new, but I find that many people don't know about the PostgreSQL row lock modes. So here I'll write up a detailed explanation to let you know when to avoid SELECT FOR UPDATE.

SELECT FOR UPDATE: avoiding lost updatesData modifying statements like UPDATE or DELETE lock the rows they process to prevent concurrent data modifications. However, this is often too late. With the default isolation level READ COMMITTED, there is a race condition: a concurrent transaction can modify a row between the time you read it and the time you update it. In that case, you obliterate the effects of that concurrent data modification. This transaction anomaly is known as “lost update”.

If you don't want to use a higher transaction isolation level (and deal with potential serialization errors), you can avoid the race condition by locking the row as you read it:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

START TRANSACTION; /* lock the row against concurrent modifications */ SELECT data FROM tab WHERE key = 42 FOR UPDATE; /* computation */ /* update the row with new data */ UPDATE tab SET data = 'new' WHERE key = 42; COMMIT; |

But attention! The above code is wrong! To understand why, we have to dig a little deeper.

We need to understand how PostgreSQL guarantees referential integrity. Let's consider the following tables:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

CREATE TABLE parent ( p_id bigint PRIMARY KEY, p_val integer NOT NULL ); INSERT INTO parent VALUES (1, 42); CREATE TABLE child ( c_id bigint PRIMARY KEY, p_id bigint REFERENCES parent ); |

Let's start a transaction and insert a new row in child that references the existing row in parent:

|

1 2 3 |

START TRANSACTION; INSERT INTO child VALUES (100, 1); |

At this point, the new row is not yet visible to concurrent transactions, because we didn't yet commit the transaction. So a concurrent transaction could try to delete the referenced row in parent, and if our transaction would commit, that would violate the foreign key constraint. PostgreSQL has to prevent that from happening!

To protect the referenced row, the INSERT on child puts a FOR KEY SHARE lock on the referenced row in parent. The concurrent DELETE will then block, because its row lock conflicts with FOR KEY SHARE. As soon as the inserting transaction commits, the DELETE can either proceed (if the inserting transaction rolled back) or will receive a constraint violation error (if the inserting transaction committed).

UPDATE and DELETEIn the previous section we saw how PostgreSQL uses the FOR KEY SHARE row lock. The lock compatibility table shows that there are three more row locks: FOR UPDATE, FOR NO KEY UPDATE and FOR SHARE. We have to understand when PostgreSQL takes these row locks:

FOR UPDATE on rows before a DELETE, or before an UPDATE that modifies a column that is part of a unique index that neither contains expressions nor is partialFOR NO KEY UPDATE on rows before any other UPDATEFOR SHARE row lockIn short, PostgreSQL takes a FOR UPDATE lock if you modify a column that might be part of a primary key or unique constraint that could be referenced by a foreign key. Only such data modifications have the potential to conflict with an INSERT as described in the previous section. UPDATEs that don't modify a key cannot conflict with an INSERT. Such UPDATEs won't block, because FOR NO KEY UPDATE does not conflict with FOR KEY SHARE.

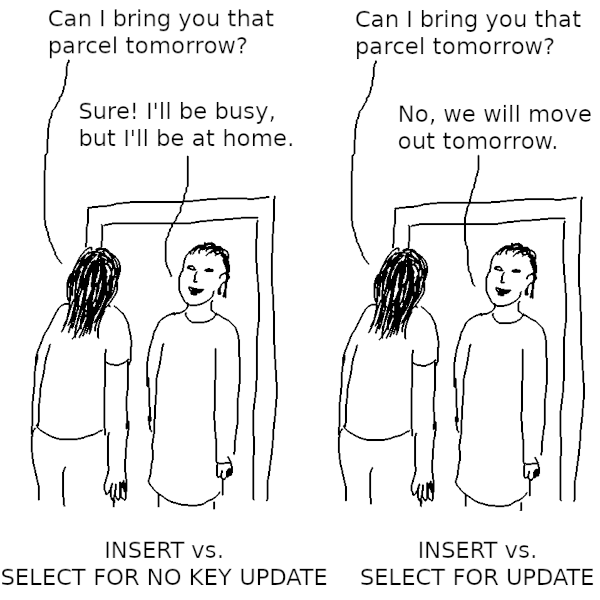

SELECT FOR UPDATE in PostgreSQLThe problem with SELECT FOR UPDATE is that the row lock it takes is usually too strong. Counter to intuition, most UPDATEs don't take a FOR UPDATE lock, because they don't conflict with a concurrent INSERT on a referencing table. If you use SELECT FOR UPDATE on a row in a table referenced by a foreign key, you will block all INSERTs that reference that row:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

/* first session */ START TRANSACTION; SELECT p_val FROM parent WHERE p_id = 1 FOR UPDATE; /* second session - will hang */ INSERT INTO child VALUES (100, 1); |

So SELECT FOR UPDATE is bad for concurrency, as it can cause unnecessary locks. Unless you plan to delete a row or modify a key column, always use SELECT FOR NO KEY UPDATE.

SELECT FOR UPDATE is not the correct row lock for an UPDATE?Yes, that is correct. This confusing fact is a historical liability. In the bad old days, PostgreSQL only had two row lock modes: FOR SHARE and FOR UPDATE. FOR UPDATE was the lock for data modifications, and FOR SHARE was the lock for referenced rows of a foreign key. Back then, an UPDATE of the referenced row always conflicted with an INSERT of a referencing row.

PostgreSQL commit 0ac5ad5134 improved that by introducing the FOR KEY SHARE and FOR NO KEY UPDATE row locks we have today. Perhaps it would have been less confusing to rename the original lock mode to FOR KEY UPDATE and repurpose FOR UPDATE for the new, weaker lock mode. However, that ship has sailed long ago.

Unless you plan to delete a row or modify a key column, you should use SELECT FOR NO KEY UPDATE. That way you won't block concurrent INSERTs of a referencing row.

Thank you for this article. In IBM Db2 database if using normal "SELECT...FOR UPDATE" executes ordinary "SELECT" as it was written without "FOR UPDATE". In Db2 if you want to use "FOR UPDATE" you need to specify cursor. "DECLARE mycursor CURSOR FOR SELECT... FOR UPDATE", then "OPEN mycursor" and "FETCH mycursor" and when FETCH is executed a row is locked and another session update of this row is in wait state. In IBM Db2 "SELECT... FOR UPDATE" also locks all of the columns, if you want to lock specific columns you set them as "SELECT...FOR UPDATE OF column1, column2". In this respect "SELECT...FOR UPDATE" in PostgeSQL is in consistent behaviour (locking all the columns) with IBM Db2 and this is nice to know, when programmer is working on both databases. Inconsistencies are the most dangerous, because user expect something, but something else happens.