UPDATED blog article on 09.01.2023

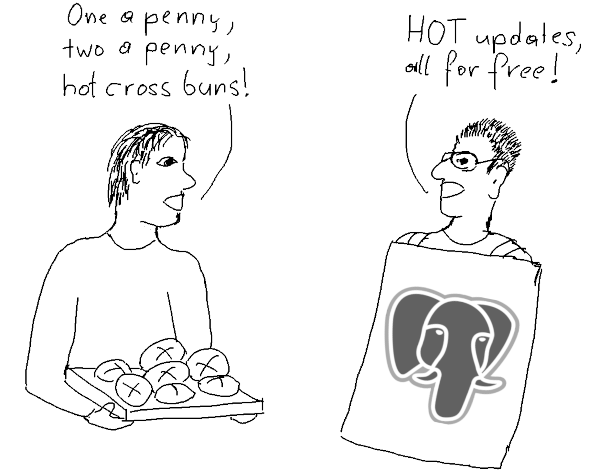

HOT updates are not a new feature. They were introduced by commit 282d2a03dd in 2007 and first appeared in PostgreSQL 8.3.

Table of Contents

But since HOT is not covered by the PostgreSQL documentation (although there is a README.HOT in the source tree), it is not as widely known as it should be: Hence this article that explains the concept, shows HOT in action and gives tuning advice.

HOT is an acronym for “Heap Only Tuple” (and that made a better acronym than Overflow Update CHaining). It is a feature that overcomes some of the inefficiencies of how PostgreSQL handles UPDATEs.

UPDATEPostgreSQL implements multiversioning by keeping the old version of the table row in the table – an UPDATE adds a new row version (“tuple”) of the row and marks the old version as invalid.

In many respects, an UPDATE in PostgreSQL is not much different from a DELETE followed by an INSERT.

This has a lot of advantages:

ROLLBACK does not have to undo anything and is very fastBut it also has some disadvantages:

VACUUM)Essentially, UPDATE-heavy workloads are challenging for PostgreSQL. This is the area where HOT updates help. Since PostgreSQL v12, we can extend PostgreSQL to define alternative way to persist tables. zheap, which is currently work in progress, is an implementation that should handle UPDATE-heavy workloads better.

UPDATE exampleLet's create a simple table with 235 rows:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

CREATE TABLE mytable ( id integer PRIMARY KEY, val integer NOT NULL ) WITH (autovacuum_enabled = off); INSERT INTO mytable SELECT *, 0 FROM generate_series(1, 235) AS n; |

This table is slightly more than one 8KB block long. Let's look at the physical address (“current tuple ID” or ctid) of each table row:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

SELECT ctid, id, val FROM mytable; ctid | id | val ---------+-----+----- (0,1) | 1 | 0 (0,2) | 2 | 0 (0,3) | 3 | 0 (0,4) | 4 | 0 (0,5) | 5 | 0 ... (0,224) | 224 | 0 (0,225) | 225 | 0 (0,226) | 226 | 0 (1,1) | 227 | 0 (1,2) | 228 | 0 (1,3) | 229 | 0 (1,4) | 230 | 0 (1,5) | 231 | 0 (1,6) | 232 | 0 (1,7) | 233 | 0 (1,8) | 234 | 0 (1,9) | 235 | 0 (235 rows) |

The ctid consists of two parts: the “block number”, starting at 0, and the “line pointer” (tuple number within the block), starting at 1.

So the first 226 rows fill block 0, and the last 9 are in block 1.

Let's run an UPDATE:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

UPDATE mytable SET val = -1 WHERE id = 42; SELECT ctid, id, val FROM mytable WHERE id = 42; ctid | id | val --------+----+----- (1,10) | 42 | -1 (1 row) |

The new row version was added to block 1, which still has free space.

To understand HOT, let's recapitulate the layout of a table page in PostgreSQL:

The array of “line pointers” is stored at the beginning of the page, and each points to an actual tuple. This indirect reference allows PostgreSQL to reorganize a page internally without changing the outside appearance.

A Heap Only Tuple is a tuple that is not referenced from outside the table block. Instead, a “forwarding address” (its line pointer number) is stored in the old row version:

That only works if the new and the old version of the row are in the same block. The external address of the row (the original line pointer) remains unchanged. To access the heap only tuple, PostgreSQL has to follow the “HOT chain” within the block.

There are two main advantages of HOT updates:

VACUUM.If there are several HOT updates on a single row, the HOT chain grows longer. Now any backend that processes a block and detects a HOT chain with dead tuples (even a SELECT!) will try to lock and reorganize the block, removing intermediate tuples. This is possible, because there are no outside references to these tuples.This greatly reduces the need for VACUUM for UPDATE-heavy workloads.There are two conditions for HOT updates to be used:

The second condition is not obvious and is required by the current implementation of the feature.

fillfactor on tables to get HOT updatesYou can make sure that the second condition from above is satisfied, but how can you make sure that there is enough free space in table blocks? For that, we have the storage parameter fillfactor. It is a value between 10 and 100 and determines to which percentage INSERTs will fill a table block. If you choose a value less than the default 100, you can make sure that there is enough room for HOT updates in each table block.

The best value for fillfactor will depend on the size of the average row (larger rows need lower values) and the workload.

Note that setting fillfactor on an existing table will not rearrange the data, it will only apply to future INSERTs. But you can use VACUUM (FULL) or CLUSTER to rewrite the table, which will respect the new fillfactor setting.

There is a simple way to see if your setting is effective and if you get HOT updates:

|

1 2 3 4 |

SELECT n_tup_upd, n_tup_hot_upd FROM pg_stat_user_tables WHERE schemaname = 'myschema' AND relname = 'mytable'; |

This will show cumulative counts since the last time you called the function pg_stat_reset().

Check if n_tup_hot_upd (the HOT update count) grows about as fast as n_tup_upd (the update count) to see if you get the HOT updates you want.

Let's change the fillfactor for our table and repeat the experiment from above:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

TRUNCATE mytable; ALTER TABLE mytable SET (fillfactor = 70); INSERT INTO mytable SELECT *, 0 FROM generate_series(1, 235); SELECT ctid, id, val FROM mytable; ctid | id | val ---------+-----+----- (0,1) | 1 | 0 (0,2) | 2 | 0 (0,3) | 3 | 0 (0,4) | 4 | 0 (0,5) | 5 | 0 ... (0,156) | 156 | 0 (0,157) | 157 | 0 (0,158) | 158 | 0 (1,1) | 159 | 0 (1,2) | 160 | 0 (1,3) | 161 | 0 ... (1,75) | 233 | 0 (1,76) | 234 | 0 (1,77) | 235 | 0 (235 rows) |

This time there are fewer tuples in block 0, and some space is still free.

Let's run the UPDATE again and see how it looks this time:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

UPDATE mytable SET val = -1 WHERE id = 42; SELECT ctid, id, val FROM mytable WHERE id = 42; ctid | id | val ---------+----+----- (0,159) | 42 | -1 (1 row) |

The updated row was written into block 0 and was a HOT update.

HOT updates are the one feature that can enable PostgreSQL to handle a workload with many UPDATEs.

In UPDATE-heavy workloads, it can be a life saver to avoid indexing the updated columns and setting a fillfactor of less than 100.

If you are interested in performance measurements for HOT updates, look at this article by Kaarel Moppel.

In order to receive regular updates on important changes in PostgreSQL, subscribe to our newsletter, or follow us on Twitter, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

+43 (0) 2622 93022-0

office@cybertec.at

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Facebook. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationYou are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information

This was really interesting and helpful. Thank you!

Hello! I know this article is kind of old but I'm left wondering, what happens when the block eventually fills?

As seen in the final experiment, the HOT update inserts the updated value at the latest available block space (0,159). Now, if I make a lot of updates, then the block will eventually fill, what happens then? Is the updated value inserted in the last available space on the next block? if that's so, what happens to the index?

Thanks for making this really informative post!:)

An

INSERTwill never fill the block if thefillfactoris less than 100.If there is not enough room in any of the existing pages, PostgreSQL will extend the table.

HOT update only applies to updates. There is no guarantee that HOT update is used: if there is not enough room in the same page, PostgreSQL will perform a regular

UPDATEand modify the index.Thanks for the good article. You said "Dead tuples can be removed without the need for VACUUM.", can a snapshot conflict arise if there is a query running on the slave when HOT Pruning is executed in msater?

Yes, absolutely, because it removes row versions.

You can consider setting

hot_standby_feedback = onon the standby orvacuum_defer_cleanup_ageto a value greater than 0 on the primary to reduce the number of snapshot conflicts.Assuming that the fill-factor is < 100 and the block gets completely filled due to a lot of HOT updates, can the block get free space back after vacuum runs to accommodate more HOT updates in future? Thanks for the wonderful article!

Yes, a

VACUUMwill free up space within the block (if HOT chain pruning hasn't already done it).Hi,

Thanks for the great article. I have some open questions. Could you please clarify it?

- A sample query is provided in the article to see if settings would be effective or not. So could you please guide me what ratio of (n_tup_upd / n_tup_hot_upd) means to go for hot updates? Would ratio (n_tup_upd = 517,244,309 / n_tup_hot_upd = 39,062,809) ~13 means to spend effort for enabling hot update?

- Would enabling hot updates have impact on read performance?

- Regarding this point "there is no index defined on any column whose value it modified", would this mean that a table should only have indices whose value can't be modified? For instance, a table can have 2 indices. For one of the indices, it's ensured that its value wouldn't change. But there is no guarantee for the other index.

In your example, less than a tenth of the

UPDATEs are HOT. So you could expect performance improvements by HOT updates.HOT updates don't directly influence read performance. But they keep index fragmentation low, which can benefit index range scans.

You can modify an indexed column, but then you won't get a HOT update. The goal is not necessarily to make all updates become HOT. If updates of an indexed column are rare, it does not matter much. If you need an index on a column that is modified by most of the updates, you won't benefit from HOT. It is the old choice: speeding up reads can slow down writes and vice versa.

Hi,

Thanks for your response. I am playing with it to upderstand it better.

So, I modified index column and I still have a hot update. Could you please tell me what am I doing wrong? Or did I misunderstand something?

Here is a table definition:

CREATE TABLE public.my_ages (

age int8 NOT NULL,

"name" varchar NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT my_ages_pkey PRIMARY KEY (age)

)

WITH (

autovacuum_enabled=off,

fillfactor=70

);

CREATE INDEX my_ages_name_idx ON public.my_ages USING btree (name);

and contains the following data

INSERT INTO my_ages

SELECT n, 'My name' || '-' || n

FROM generate_series(1, 235) AS n;

Original state (without update)

"ctid","age","name"

"(0,1)",1,My name-1

Now updating indexed colum results in HOT update.

update my_ages

set "name" = 'My awesome name 1'

where "name" = 'My name-1'

Now, fetching it

SELECT ctid, *

FROM my_ages ma

where age = 1;

OR via

SELECT ctid, *

FROM my_ages ma

where "name" = 'My awesome name 1'

gives the following results.

"ctid","age","name"

"(0,110)",1,My awesome name 1 <---- here it is still updating this row on the same block.

Just because the new version ends up on the same page doesn't make it a HOT update.

Hi,

Thanks. So, if I understand it correctly ... the overall goal for this HOT update is to reduce (table & index) bloat. This improves overall performance of cluster.

Is my understanding correct?

I find it useful feature but I am still not able to understand this "not modifiying indexed column" condition completely. I am not sure the consequences after rolling it our to production system.

I think bloating can also be controlled (or cleaned up) via "REINDEXING" (for indexes) or "Vacuuming" (for table) and can improve cluster performance. Correct?

Correct, the goal is improved update performance, reduced index bloat and less need for autovacuum.

About modifying an indexed column: A heap-only tuple is referenced from nowhere outside the page where it lives. That's why removing a dead heap-only tuple is so simple. Now if you update an indexed column, the index needs to get a new entry that references the tuple, so it is no longer a heap-only tuple.

Sure, index bloat can also be combatted with

REINDEX CONCURRENTLY, but that's an extra task you have to schedule.Do you already know that you will get in trouble without HOT updates or

REINDEX? If not, my advice is to tune autovacuum to run fast on the table in question. Often that is good enough.